Principles of Liberty: Ten Biblical Truths Embedded in the Declaration of Independence

A Five-Session Bible Study

Background Information for Session 2

The Relationship of God’s Laws to Human Happiness and Human Worth

The Quest to Rediscover the Founders’ Perspective

This Bible study series is based on the Word Foundations post titled “Principles of Liberty.” The article highlights ten biblical principles embedded in the Declaration of Independence.

The Bible study series consists of five sessions, with each one exploring two principles.

This article provides background information for the second session. A teaching plan is available here.

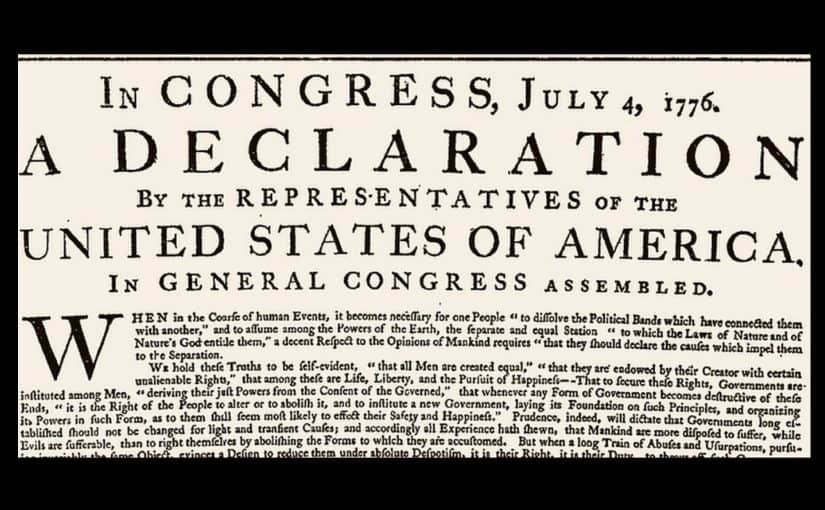

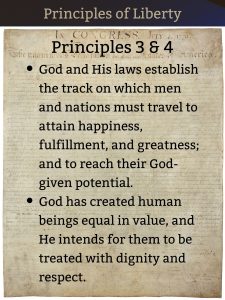

A PDF file of the above graphic is available here.

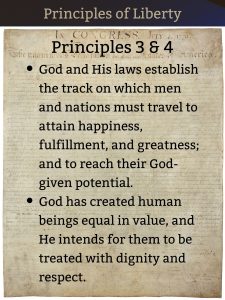

It’s high time we rediscover the true meaning of these principles and that we contend anew for them as the Founders understood them. In our series, we’re highlighting words and phrases from the most quoted portion of the Declaration, then we’re demonstrating how they’re linked to Scripture and to biblical truth. In this session (the second of five), we’ll be considering the third and fourth principles.

A PDF file of this graphic is available here.

A PDF file of this graphic is available here.

PRINCIPLE THREE

God and His laws establish the track on which men and nations must travel to attain happiness, fulfillment, and greatness; and to reach their God-given potential.

In our main article, we stated this about the third principle.

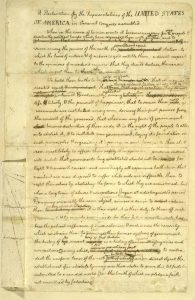

While the Declaration of Independence frames this principle in the context of Colonial opposition to British tyranny and the forming of a new nation to secure and protect citizens’ inherent rights, the lesson has an even broader application. Both people and governments are accountable to God. Our Founders knew that men and women cannot live fulfilled lives by merely following their whims and desires, treading down whatever paths their raw appetites direct them. Rather, they must “assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them.” The word entitle is important here, and it appears both in Jefferson’s draft [here] and in the final document [here]. Entitle as the Founders used it is light years away from the meanings it and its various forms frequently carry today. How do we know this? Because according to the men who ratified the Declaration, that to which the people are entitled is granted and governed according to “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God.” By contrast, today, people look to government for everything to which they believe they are “entitled.”

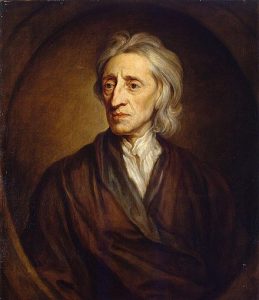

According to an article at conservapedia.com (which we cited in the background material for Session One), “The Declaration of Independence drew upon Christianity and the Enlightenment English philosopher John Locke.” Though Locke often is described just as this article characterizes him — as an “Enlightenment English philosopher” — John Locke’s thinking actually had biblical and theological underpinnings, even bringing him to a point at which “he was considered a theologian by his peers and by subsequent generations.” This is not to say that all his views aligned with Scripture, but that he cannot accurately be thought of as a purely secular philosopher. In his influential work Two Treatises of Government, published in 1689 — a work from which the Founders who wrote and ratified the Declaration drew — Locke said this: “The end of law is not to abolish or restrain, but to preserve and enlarge freedom.”

The end of law is not to abolish or restrain, but to preserve and enlarge freedom.

—John Locke—

This idea hits hard against the concepts of freedom and autonomy prevailing in America today. Shortly before his death in 1984, Christian philosopher Francis Schaeffer observed, “[T]he problem of the 1920s to the 1980s…is the attempt to have absolute freedom—to be totally autonomous from any intrinsic limits. It is the attempt to throw off anything that would restrain one’s own personal autonomy. But it is especially a direct and deliberate rebellion against God and his law.”

The problem of the 1920s to the 1980s…is the attempt to have absolute freedom—to be totally autonomous from any intrinsic limits. It is the attempt to throw off anything that would restrain one’s own personal autonomy. But it is especially a direct and deliberate rebellion against God and his law.

—Francis Schaeffer—

Once again, here is the third principle.

God and His laws establish the track on which men and nations must travel to attain happiness, fulfillment, and greatness; and to reach their God-given potential.

Let’s explore this idea using the following illustrations involving three members of the animal kingdom: first a dachshund and a hamster, and then a crab.

The Dachshund and the Hamster

In a Family TalkTM booklet titled Discipline, Dr. James Dobson relates a story loaded with lessons for us today. Countering the idea that parents and their children should “be on an even playing field—making decisions by negotiation and compromise,” Dobson recalls observing his daughter’s pet hamster fidgeting in his cage, anxiously trying to escape. The little guy

worked tirelessly to open the gate and push his furry little nose between the bars. Then I noticed our dachshund, Siggie, sitting eight feet away in the shadows. He was watching the hamster, too. His ears were erect, and it was obvious what was on his mind. He was thinking, Come on, baby. Open that door, and I’ll have you for lunch. If the hamster had been so unfortunate as to escape from his cage, which he desperately wanted to do, he would have been dead in a matter of seconds.

Dobson goes on to discuss the difference between the hampster’s perspective and his own: “I was aware of dangers that he couldn’t have foreseen. That’s why I denied him something that he desperately wanted to achieve.”

In this respect, children are like that hampster—but so is everyone else in the human race, regardless of age, before he or she is willing to acknowledge the big picture offered by “Nature and…Nature’s God,” to quote the Declaration of Independence.

But wait! The Declaration does not just speak of “Nature and…Nature’s God,” but of “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God” (emphasis added). What? In the Declaration of Independence? Yes! Our founders got it right. True freedom and liberty—on both personal and societal levels—can be established and maintained only when individuals and society affirm the laws of nature, or absolute truth. Dr. Dobson’s perspective in relation to his daughter’s hamster parallels the one we need with regard to the world, life, and the universe.

True freedom and liberty—on both personal and societal levels—can be established and maintained only when individuals and society affirm the laws of nature, or absolute truth.

Even a relativist has to admit that some truths and falsehoods exist.

-

-

- He knows he’s wearing a blue shirt and not a red one.

- She lives in Texas, not in Vermont.

- Go through a traffic intersection when you approach a green light, not a red one. In fact, doing otherwise will invite danger and even can be deadly.

-

Truths and falsehoods in the moral and spiritual realms exist, too. These also are evident, but we don’t recognize them with physical senses like seeing and hearing—yet they can be even more consequential than realities in the physical realm.

The Crab

In their book on apologetics for high schoolers titled Don’t Check Your Brains at the Door, Josh McDowell and Bob Hostetler expose 42 myths that have become quite popular in today’s culture. One of them is the “Anarchist Myth.”1 To expose this false belief for the lie it really is, McDowell and Hostetler tell a story. The story also is available online.

Herman, the son of a crab named Fred, was growing rather weary of what he believed to be the confinement imposed on him by his shell. “Hey, Dad! This shell is really boxing me in,” said Herman. “I can’t take it anymore! I want my freedom! My friends and I have been talking, and they feel the same way. Some of them are thinking about forming a group called ‘Crabs for Shedding Shells.’ I’m ready to help!”

Herman, the son of a crab named Fred, was growing rather weary of what he believed to be the confinement imposed on him by his shell. “Hey, Dad! This shell is really boxing me in,” said Herman. “I can’t take it anymore! I want my freedom! My friends and I have been talking, and they feel the same way. Some of them are thinking about forming a group called ‘Crabs for Shedding Shells.’ I’m ready to help!”

“Son,” said Fred to his boy, “I understand your frustration. I know it’s easy for you to think your shell is denying you freedom and that you could move around unencumbered if you only could get rid of it—but let me tell you a story.”

“Aww, Dad, come on. I’m too old for that!” complained Herman.

“Now, hear me out,” replied the elder crab. “I think this will make a lot of sense to you. My story is about

Humphrey the human, who insisted on going barefoot to school. He complained that his shoes were too confining. They cramped his style, he said. He longed to be free to run barefoot through fields and streams. Finally, his mother gave in to him. He skipped out of the house barefoot. Do you know what happened?”

Herman opened his mouth, but his father continued before he could answer.

“Humphrey the human stepped on pieces of a broken bottle. His foot required twenty stitches, and some other guy took his girl to the prom while Humphrey sat home watching reruns of Flipper.”

“That’s a pretty lame story, Dad,” Herman said.

“Maybe, Son, but the point is this: Every crab has felt this way at one time or another, thinking life would be better if he could be completely shell-free. But that’s like a sailor getting tired of the confinement of a ship and jumping to freedom in the sea. He may think that’s freedom, but if he doesn’t get back to ship or shore, he’ll drown and end up as crab food. What kind of freedom is that?”

Fred explained to Herman that one day in the not-too-distant future, he indeed would discard his shell. The process, called molting, is a normal part of a crab’s growth into adulthood. “But don’t be fooled,” Fred warned his son. “After your old shell comes off, you’re going to be especially vulnerable. It’ll be a dangerous time. You’ll need to be more careful than ever until your new shell hardens.” Fred tapped his son’s exterior shield a couple of times and then summarized his main point. “The truth, Herman, is that without a protective shell, life will be far more confining than liberating.”

Both the irony and the reality of the situation were beginning to dawn on Herman. After thoughtful reflection, he turned to his dad and said,

“You mean that some things may seem to limit freedom but really make greater freedom possible?”

Fred smiled broadly and patted his son on the back with a mammoth claw. “How’d you get to be so smart, Son?” he asked.

Corporate Liberty Depends on the Affirmation of a Supreme Authority

“The Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God” are like Herman’s shell. Coming back now to the larger picture, we note that as a nation, if we don’t return to these laws, we will lose our liberty. Does everyone have to become a Christian in this nation for America to restore and maintain liberty? No, not everyone was a Christian even at America’s founding, although most were. People believed in God, however, and that was key. In particular, the Founders held beliefs “rooted in the Judeo-Christian values found in the Bible.”

The prevalence of these attitudes at the founding of the United States of America brings to mind this passage from Deuteronomy 30:11-20. This charge was given to the Israelites around the time the nation of Israel was established when God gave His people the promised land. In verses 15-20 God said to His people through Moses,

15 “See, I have set before you today life and good, death and evil, 16 in that I command you today to love the Lord your God, to walk in His ways, and to keep His commandments, His statutes, and His judgments, that you may live and multiply; and the Lord your God will bless you in the land which you go to possess. 17 But if your heart turns away so that you do not hear, and are drawn away, and worship other gods and serve them, 18 I announce to you today that you shall surely perish; you shall not prolong your days in the land which you cross over the Jordan to go in and possess. 19 I call heaven and earth as witnesses today against you, that I have set before you life and death, blessing and cursing; therefore choose life, that both you and your descendants may live; 20 that you may love the Lord your God, that you may obey His voice, and that you may cling to Him, for He is your life and the length of your days; and that you may dwell in the land which the Lord swore to your fathers, to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, to give them.”

I call heaven and earth as witnesses today against you, that I have set before you life and death, blessing and cursing; therefore choose life, that both you and your descendants may live; that you may love the Lord your God, that you may obey His voice, and that you may cling to Him, for He is your life and the length of your days; and that you may dwell in the land which the Lord swore to your fathers, to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, to give them.

—God, through Moses, to the Israelites as they were on the cusp of entering the promised land—

“I will walk at liberty,” wrote the pslmist in Psalm 119:45, “For I seek Your precepts.”

“Entitle”

We need to say just a few more things about the Founders’ use of the word entitle. The Declaration of Independence declares,

When in the Course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

As we mentioned earlier, the meaning of the word entitle as the Founders used it in this context is a far cry from the notion so often employed when people use the term today. Frequently today, the word is used to convey the idea of laying a claim to or having a right to something the government offers or “provides” — and this is the primary, if not the only, emphasis.

We must remember that the men who authorized the Declaration and the severing of political ties from Great Britain the Declaration affirmed looked to “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God” as the basis for the recognition to which the new nation would be entitled. The thirteen colonies now were becoming thirteen states and a new country — The United States of America. That country, under God’s laws, would hold a just claim to be seen by its mother country and all the other nations on the earth as “separate and equal,” not inferior. Put slightly differently, the new nation would have the right to “assume” a “separate and equal” position or “station” among the countries of the world.

This entitlement has a parallel in the “unalienable rights” to which the Declaration soon would refer. Another important point is that both the rights and the recognition or respect that God grants both individuals and nations cannot be separated from responsibilities that also are God-given. The Declaration mentions one of those responsibilities immediately: “a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they [the people severing ties they have had with one nation to form another] should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.”

Later we will explore the meaning and the nature of the rights the Founders upheld in America’s “birth certificate.” We will see that those God-given rights inherently demand responsibilities, both of citizens and the government.

For now, notice that the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence were not referring at all to government entitlements, but to rights granted under “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God.”

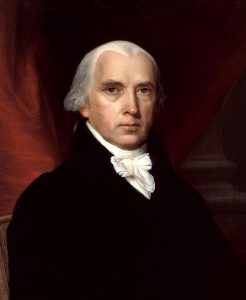

James Madison (1751-1836) declared, “We have staked the whole future of American civilization, not upon the power of government, far from it. We’ve staked the future of all our political institutions upon our capacity…to sustain ourselves according to the Ten Commandments of God.”

Robert Winthrop (1809-1894) said this to the Annual Meeting of the Massachusetts Bible Society in Boston, Massachusetts, on May 28, 1849: “All societies of men must be governed in some way or other. The less they may have of stringent State Government, the more they must have of individual self-government. The less they rely on public law or physical force, the more they must rely on private moral restraint. Men, in a word, must necessarily be controlled, either by a power within them, or by a power without them; either by the Word of God, or by the strong arm of man; either by the Bible, or by the bayonet. It may do for other countries and other governments to talk about the State supporting religion. Here, under our own free institutions, it is Religion which must support the State.”

PRINCIPLE FOUR

God has created human beings equal in value, and He intends for them to be treated with dignity and respect.

Before we examine this idea directly and show how it reflects biblical teachings, we need to became aware of ways Americans are being misled about both the founding of the United States and the beliefs of the men who established it. One really awesome way to consider this is with a brief review of a monumental event in American history that began when the country was less than thirty years old—the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The point we make is that we cannot get an accurate picture of history if we interpret it based on 21st-century experiences and perspectives. The illustration we provide is is helpful, but optional. You can access it here.

Sadly, quite often, sloppy historians and agenda-driven politicians interpret the past through the lens of modern perspectives on everything from medicine to the economy to social status. As they do, they make a multitude of unwarranted and often condescending judgments. H. L. Mencken, a writer known for his own brand of sensationalism, once said that a historian is “an unsuccessful novelist.” Unfortunately, he was all too accurate.

Historian: an unsuccessful novelist.

—H. L. Mencken—

When Studying History, Remember These Guidelines

As we soon will see, distortions of historical events in America’s past have become manipulative tools to fuel societal tension and racial division in modern America. We must first approach history with the right interpretative perspective. Here are some important guidelines:

-

-

- Learn all you can, not just about what happened, but also about what led up to it.

- Seek to understand the thinking of the times. Do not blame the people of a past era for not knowing pertinent information we know today, especially information they had no way to learn.

- Remember that we have hindsight, and they did not. Some even possessed a lot more foresight than we tend to believe.

- Look beyond surface meanings and consider implications and repercussions.

- Consider the worldview perspectives of historical subjects.

- Don’t just observe what people did, but also take note what they didn’t do.

-

If we will seek to do these things, the lessons we derive from history’s vaults will be far more accurate than they otherwise would.

A PDF file of the above graphic is available here.

With these guidelines in mind, we move now to consider the fourth principle on our list.

God has created human beings equal in value, and He intends for them to be treated with dignity and respect.

This principle is derived from these immortal words in the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” In our main article, we said this:

Inevitably, someone will ask, Why did the Founders say this but not abolish slavery? It’s an important question. Yet to be fair we must

evaluate our Founders not in light of our own culture, but in light of theirs; America’s “Founders were born into a society that permitted slavery.”2 Despite this, some swam against the tide as they expressed resistance and even opposition to the practice.

Thomas Jefferson, himself a slaveowner, was one such man. In his original draft of the Declaration, he took the King of England to task for his role in the slave trade.…

We can scratch our heads in bewilderment over what to us appears to be Jefferson’s hypocrisy; but more realistically, doesn’t it appear that these are the actions of a man whose conscience has been stirred, but who knows he cannot overturn this aspect of the cultural landscape in a split second?…

Jefferson’s own involvement in the institution of slavery was deep, yet not fully because of his own conscious choices.… [T]he Virginian was born at a time when slavery was the order of the day. Can we not understand he personally finds it difficult at one moment in time to do a complete about-face regarding the matter?

It is true the delegates to the Second Continental Congress struck Jefferson’s proposed section against King George regarding the slave trade and thereby prevented it from being included in the final document. Generally speaking, the men who represented the southern states were pro-slavery and worked to preserve it. This kept the Declaration from condemning slavery and the slave trade outright. Even so, ideas the Declaration explicitly did state, especially the beliefs “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness,” in fact constituted an implicit condemnation of slavery. Remarkably, this turned out to be an even more forceful condemnation of slavery and racism than anything else Jefferson had proposed.

Were America’s Founders Racists?

Many people who contend the Founders were racists point not primarily to the Declaration of Independence, but to the Constitution of 1787 and the so-called “Three-Fifths Clause” it contained.

Obviously, slavery continued in America for many years after the Declaration was adopted in 1776 and beyond the point Constitution took effect in 1789, but this fact alone does not tell entire story. A great deal is at stake here. The belief that the signers of the Declaration and the Framers of the Constitution wanted slavery to continue forever understandably will make it harder for blacks to trust governmental authorities, including police. Yet, if we dig deeper and come to understand many of the relevant historical details, we just might discover truths that can help ease some of today’s racial tensions and conflicts.

Perhaps no provision in the Constitution as it was originally drafted is more misunderstood than the “Three-Fifths Clause,” which resulted from the “Three-Fifths Compromise.” While it is technically correct to say the Constitution originally authorized counting each slave as three-fifths of a person, this leaves the erroneous impression that the delegates to the Constitutional Convention and the Founders of America believed that a slave was less than a human being.

It’s important that we debunk the myth that the Constitution’s Three-Fifths Cause, in and of itself, is clear evidence that the Constitution’s Framers considered a black man or woman as less than a person. To do this, we need to examine the Three-Fifths Clause, what it authorized, why it was adopted, and the context in which it was approved. Fasten your seat belts! Here we go!

In a Word Foundations post dated May 20, 2016, we said this about the dawn of the US government under the Constitution (not all original citations have been included here).

After the American Revolution, the thirteen states rejoiced over their independence, but they still were thirteen individual states, each of which, in many ways, acted as an individual country. Previously the war against Great Britain had united these Virginians, New Yorkers, Pennsylvanians, Marylanders, and the residents of the other states, but now other matters confronted the new nation. How could the states work together? Could they establish a central government that would acknowledge states’ sovereignty, yet unify the states to address the issues that would confront them all?

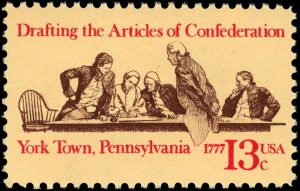

An attempt was made in the Articles of Confederation. This document was drafted under the authority of the Second Continental Congress, which appointed a committee to begin the work on July 12, 1776. In the latter part of 1777, a document was sent to the states for ratification. All the states had approved it in the early part of 1781. The states now had a new central government, but it wasn’t long before problems arose. The national government was too weak. It had no executive authority and no judiciary. Too high a hurdle had been established for the passage of laws. Furthermore, the states had their own monetary systems, so understandably, buying and selling across state lines became difficult. Without free trade between the states, the national economy was severely hindered.…

Accordingly, the states were asked to send their representatives to Philadelphia in May of 1787. This meeting become the Constitutional Convention. Delegates soon realized they shouldn’t try to fix the Articles of Confederation but needed to replace it altogether. The Convention met from May 25 to September 17, 1787.

According to Article VII of the proposed Constitution, the document would become binding on all thirteen states after it had been ratified by nine. New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify on Saturday, June 21, 1788. The remaining states followed, but after New Hampshire’s decisive vote it was “agreed that government under the U.S. Constitution would begin on March 4, 1789.” Thus, the last two states to ratify, North Carolina and Rhode Island, did so after the Constitution already had taken effect. On November 21, 1789, North Carolina officially embraced the Constitution, and on May 29, 1790, by just two votes, Rhode Island joined the rest of the original colonies, making it unanimous.

Hammering Out the Details of the Constitution for the New Nation

When the Constitution was being drafted in 1787, however, approval by the thirteenth of thirteen states was three years and a great many debates away. As they hammered out the details, delegates crafted a Constitution that differed from the Articles of Confederation in a large number of ways. One of these related to the legislative body. Some delegates, principally those from the small states, felt each state should have an equal share of lawmakers. Others, mainly those from the larger states, believed that representation in the legislative body should reflect each state’s population. The Articles of Confederation had set up just one legislative body, but the new Constitution established two—the Senate and the House of Representatives. This arrangement affirmed both perspectives. In the Senate, each state, regardless of size, would have two Senators. In the House, the number of representatives from each state would be determined by that state’s population. Thus, in the House, the larger states would have more representatives than the smaller ones. For a bill to become law, it would have to pass both houses of Congress. This truly was was a brilliant approach.

Having agreed to this model, the delegates then had to adopt a formula for determining the number of representatives each state would have in the House. Delegates resolved that each state would get one Representative for every 30,000 people. Even though only men could vote at that time, women and children were counted along with them. But how should slaves be counted? Gary DeMar writes, “The Northern states did not want to count slaves. The Southern states hoped to include slaves in the population statistics in order to acquire additional representation in Congress to advance their political [pro-slavery] position.” In the end, it was agreed that in slave states, a Representative would be added for every 50,000 slaves rather than 30,000. In mathematical terms, this effectively meant that that every five slaves would count as three persons for representation purposes, so each individual slave would be counted as three-fifths of a person. This same count also was used to determine amounts states would pay in taxes as well.

As insensitive and as cruel as this may sound in our day, this was not at all about the worth of a slave as a person. Had the Southern states gotten what they wanted, every slave would have been counted as one individual. This would have resulted in a stronger pro-slavery contingent in the House. Had the Northern states gotten their way, no slaves would have been counted at all, and the anti-slavery position in the House of Representatives would have been strengthened to the greatest degree possible. Neither side prevailed. A compromise was reached.

The Three-Fifths Clause read,

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.

ARTICLE I, SECTION 2, CLAUSE 3

So, contrary to first impressions, the pro-slavery position was to count slaves as full individuals, and the abolitionist position was to not count them at all! Again, the decision to number slaves in the manner described in the Three-Fifths Clause had absolutely nothing to do with the worth of a slave as a person, but with taxation and with representation of slave states in the House of Representatives.

The pro-slavery position was to count slaves as full individuals, and the abolitionist position was to not count them at all! The Three-Fifths Clause had absolutely nothing to do with the worth of a slave as a person, but with taxation and with representation of slave states in the House of Representatives.

Overcoming Attempts to Distort History

Overcoming the impression one gets when he or she hears that the Constitution authorized counting each slave as three-fifths of a person is difficult enough, but even many of the sources that acknowledge the Three-Fifths Clause was about counting slaves for representative and taxation purposes don’t explain what this actually meant in practical terms (as we have here). Moreover, the sources often go on to condemn, either directly or by implication, the Founders for refusing to draw a line in the sand to end slavery altogether. Consider this description of the Three-Fifths Compromise in “The Making of America: Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of a Nation.”

The Southern states insisted that their slave populations would be counted when assigning seats in the House of Representatives, even though no one seriously considered giving the right to vote to anyone other than white men. This resulted in the “Three-Fifths Compromise,” in which 60% of a state’s slave population would be added to its free population when assigning seats in the House. Sadly, the new nation’s founding document sanctioned slavery: at the insistence of Southern states, the Constitution specifically prohibited Congress from passing any laws that abolished or restricted the slave trade until 1808.3

This makes it sound as if the Southern states got everything they wanted, but, in fact (as we already have said), they did not. Moreover, the last sentence in the above paragraph is misleading in several specific ways. One of these is this: It is true that the Slave Trade Clause, which allowed the slave trade to continue for two more decades, did not require Congress to pass legislation eliminating it in 1808 but permitted it to do so. Yet on March 2, 1807, Congress did just that, and President Thomas Jefferson signed it into law. The act took effect on January 1, 1808.

Returning to the Three-Fifth’s Clause, there’s something else we must realize, and it’s very important. Under the provisions of this section of the Constitution, any slave state genuinely interested in increasing its influence in the House of Representatives and in the electoral college could bolster it easily. States that freed their slaves would increase their political strength because former slaves—individuals who now were free—would be fully counted, irrespective of their race. The Constitution of 1787 did never did mention race, slaves, or slavery.

Decades would pass before slavery finally would be eliminated, but the Constitution of 1787, and the Declaration of Independence before it, actually pointed the country in the right direction.

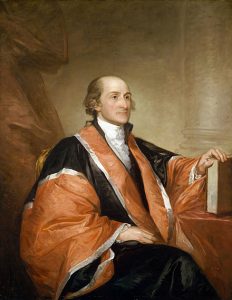

John Jay (1745-1829) became the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. He observed that before the American Revolution and the establishment of a stable government for the independent states, very little had been done to pry the institution of slavery from American life. Also, even though it would increase, the initial anti-slavery impact of Declaration of Independence was both profound and immediate. William Whipple, a signer of the Declaration from New Hampshire, “freed his slave” because he believed “that he could not both fight for liberty and own a slave.” Some believe the same man William Whipple freed, Prince Whipple, is depicted in Emanuel Leutze’s immortal 1851 painting Washington Crossing the Delaware. A black gentleman is shown in the lower left portion of the painting, rowing and seated near Washington’s right knee.

The Cost of Drawing a Line in the Sand

All Americans readily can agree that a great Civil War should not have had to occur to end slavery in America. We further can agree that blacks should not have had to endure the struggles they faced during the Civil Rights era just to be treated fairly. These realties notwithstanding, it is not true that slaves automatically would have been better off if the anti-slavery delegates at the Second Continental Congress in 1776, or those at the the Constitutional Convention in 1787, had drawn lines in the sand and refused to budge on the issue of slavery. Leftists are wont to imply anti-slavery delegates ought to be blamed for allowing slavery to continue because they did not give the pro-slavery delegates an ultimatum. Walter Williams writes,

A question that we might ask those academic hustlers who use slavery to attack and criticize the legitimacy of our founding is: Would black Americans, yesteryear and today, have been better off if the Constitution had not been ratified—with the Northern states having gone their way and the Southern states having gone theirs—and, as a consequence, no union had been created? I think not.

Mr. Williams understands that preservation of the Union under the provisions of the Constitution, and under the ideals upheld in the Declaration before it, eventually would make slaves and their descendants infinitely better off. Walter Williams continues,

Ignorance of our history, coupled with an inability to think critically, has provided considerable ammunition for those who want to divide us in pursuit of their agenda. Their agenda is to undermine the legitimacy of our Constitution in order to gain greater control over our lives. Their main targets are the nation’s youths. The teaching establishment, at our public schools and colleges, is being used to undermine American values.

Christianity and the Innate Worth of Human Beings

The idea that “all men [or persons] are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights” is thoroughly biblical. Throughout Scripture, we see that human beings are God’s highest creation and that God expects them to be accorded respect and treated with dignity. Among all the many things God brought into being, He created people alone in His own image. The Ten Commandments God gave to Israel through Moses on Mt. Sinai align perfectly with this truth. In our next session, we will explore more thoroughly God’s having created men and women, boys and girls, in His image.

The life and ministry of Jesus Christ, God’s only Son, powerfully show us how God intends for people to be treated. Jesus bucked the cultural practices and prejudices of His day to go into Samaria and talk directly to a Samaritan woman and even to stay among the Samaritans for two days. Remember, the Samaritans and the Jews hated each other, and women were considered to be inferior to men. Jesus’ actions demonstrated He had a perspective that was very different from that of the prevailing culture. Despite “the hatred between the Jews and the Samaritans, Jesus broke down the barriers between them, preaching the gospel of peace to the Samaritans (John 4:6-26), and the apostles later followed His example (Acts 8:25)” (also go here).

There’s more! Against the cultural backdrop of this racial animosity, Jesus told His parable of the good Samaritan. Having been reminded that God’s greatest commands were to love the Lord wholeheartedly and one’s neighbor as oneself, a lawyer asked this question of Jesus to “justify himself”: “And who is my neighbor?” Jesus responded to the inquiry by sharing the parable and then asked the lawyer who among the three men who had seen the man in need had acted as a neighbor to him. Unable to bring himself to utter the term Samaritan, the lawyer responded, “He who showed mercy on him.”

Both the life and teachings of Jesus advocated service to others without favoritism and without expectations of being served. The apostles also echoed these teachings.

We readily admit that America’s Founders did not perfectly apply all Jesus taught in this regard, but neither have we! Through what they affirmed in the Declaration of Independence, the Founding Fathers absolutely did uphold the biblical ideal of the dignity and worth of all people, regardless of status, race, or position in society. Furthermore, they set the stage for the eventual abolition of the institution of slavery in America and for the recognition of civil rights for all.

James Madison, a Founding Father and a slaveholder, conveyed the following in a letter to his father. He obviously was troubled about the institution of slavery as he explained he would have to sell the slave who had been accompanying him. Madison wrote, “I do not expect to get near the worth of him; but cannot think of punishing him by transportation merely for coveting that liberty for which we have paid the price of so much blood, and have proclaimed so often to be the right, & worthy the pursuit, of every human being.”

Alexander Hamilton, a Founding Father and a non-slaveholder, said this: “Man is either governed by his own laws—freedom—or the laws of another—slavery. Are you willing to become slaves? Will you give up your freedom, your life and your property without a single struggle? No man has a right to rule over his fellow creatures.”

Let’s Review

Here are the two principles from the Declaration of Independence we’ve affirmed in this session. These are the third and fourth tenets on our list.

Here are the two principles from the Declaration of Independence we’ve affirmed in this session. These are the third and fourth tenets on our list.

-

-

- God and His laws establish the track on which men and nations must travel to attain happiness, fulfillment, and greatness; and to reach their God-given potential.

- God has created human beings equal in value, and He intends for them to be treated with dignity and respect.

-

Thank you for leading your group! Have an awesome Bible study session!

A teaching plan for Session 2 is available here.

Copyright © 2020 by B. Nathaniel Sullivan. All Rights Reserved.

Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture has been taken from the New King James Version®. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Notes:

1Josh McDowell and Bob Hostetler, Don’t Check Your Brains at the Door: Know What You Believe and Why, (Dallas: Word Publishing, 1992), 179-182.

2William J. Bennett, America, the Last Best Hope—Volume 1: From the Age of Discovery to a World at War, (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2006), 122.

3The editors of Time, The Making of America, (New York: Time, Inc., 2005), 83.

image credit: Dr. James Dobson

image credit: hamster

image credit: Alexander Hamilton