The Dachshund and the Hamster

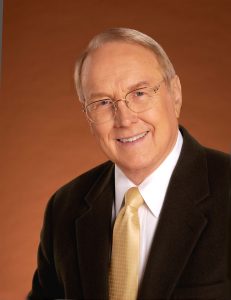

In a Family TalkTM booklet titled Discipline, Dr. James Dobson relates a story loaded with lessons for us today. Countering the idea that parents and their children should “be on an even playing field—making decisions by negotiation and compromise,” Dobson recalls observing his daughter’s pet hamster fidgeting in his cage, anxiously trying to escape. The little guy

worked tirelessly to open the gate and push his furry little nose between the bars. Then I noticed our dachshund, Siggie, sitting eight feet away in the shadows. He was watching the hamster, too. His ears were erect, and it was obvious what was on his mind. He was thinking, Come on, baby. Open that door, and I’ll have you for lunch. If the hamster had been so unfortunate as to escape from his cage, which he desperately wanted to do, he would have been dead in a matter of seconds.

Dobson goes on to discuss the difference between the hampster’s perspective and his own: “I was aware of dangers that he couldn’t have foreseen. That’s why I denied him something that he desperately wanted to achieve.”

In this respect, children are like that hampster—but so is everyone else in the human race, regardless of age, before he or she is willing to acknowledge the big picture offered by “Nature and…Nature’s God,” to quote the Declaration of Independence.

But wait! The Declaration does not just speak of “Nature and…Nature’s God,” but of “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God” (emphasis added). What? In the Declaration of Independence? Yes! Our founders got it right. True freedom and liberty—on both personal and societal levels—can be established and maintained only when individuals and society affirm the laws of nature, or absolute truth. Dr. Dobson’s perspective in relation to his daughter’s hamster parallels the one we need with regard to the world, life, and the universe.

True freedom and liberty—on both personal and societal levels—can be established and maintained only when individuals and society affirm the laws of nature, or absolute truth.

Even a relativist has to admit that some truths and falsehoods exist.

-

-

- He knows he’s wearing a blue shirt and not a red one.

- She lives in Texas, not in Vermont.

- Go through a traffic intersection when you approach a green light, not a red one. In fact, doing otherwise will invite danger and even can be deadly.

-

Truths and falsehoods in the moral and spiritual realms exist, too. These also are evident, but we don’t recognize them with physical senses like seeing and hearing—yet they can be even more consequential than realities in the physical realm.

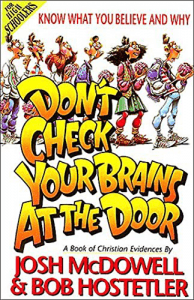

The Crab

In their book on apologetics for high schoolers titled Don’t Check Your Brains at the Door, Josh McDowell and Bob Hostetler expose 42 myths that have become quite popular in today’s culture. One of them is the “Anarchist Myth.”1 To expose this false belief for the lie it really is, McDowell and Hostetler tell a story. The story also is available online.

Herman, the son of a crab named Fred, was growing rather weary of what he believed to be the confinement imposed on him by his shell. “Hey, Dad! This shell is really boxing me in,” said Herman. “I can’t take it anymore! I want my freedom! My friends and I have been talking, and they feel the same way. Some of them are thinking about forming a group called ‘Crabs for Shedding Shells.’ I’m ready to help!”

Herman, the son of a crab named Fred, was growing rather weary of what he believed to be the confinement imposed on him by his shell. “Hey, Dad! This shell is really boxing me in,” said Herman. “I can’t take it anymore! I want my freedom! My friends and I have been talking, and they feel the same way. Some of them are thinking about forming a group called ‘Crabs for Shedding Shells.’ I’m ready to help!”

“Son,” said Fred to his boy, “I understand your frustration. I know it’s easy for you to think your shell is denying you freedom and that you could move around unencumbered if you only could get rid of it—but let me tell you a story.”

“Aww, Dad, come on. I’m too old for that!” complained Herman.

“Now, hear me out,” replied the elder crab. “I think this will make a lot of sense to you. My story is about

Humphrey the human, who insisted on going barefoot to school. He complained that his shoes were too confining. They cramped his style, he said. He longed to be free to run barefoot through fields and streams. Finally, his mother gave in to him. He skipped out of the house barefoot. Do you know what happened?”

Herman opened his mouth, but his father continued before he could answer.

“Humphrey the human stepped on pieces of a broken bottle. His foot required twenty stitches, and some other guy took his girl to the prom while Humphrey sat home watching reruns of Flipper.”

“That’s a pretty lame story, Dad,” Herman said.

“Maybe, Son, but the point is this: Every crab has felt this way at one time or another, thinking life would be better if he could be completely shell-free. But that’s like a sailor getting tired of the confinement of a ship and jumping to freedom in the sea. He may think that’s freedom, but if he doesn’t get back to ship or shore, he’ll drown and end up as crab food. What kind of freedom is that?”

Fred explained to Herman that one day in the not-too-distant future, he indeed would discard his shell. The process, called molting, is a normal part of a crab’s growth into adulthood. “But don’t be fooled,” Fred warned his son. “After your old shell comes off, you’re going to be especially vulnerable. It’ll be a dangerous time. You’ll need to be more careful than ever until your new shell hardens.” Fred tapped his son’s exterior shield a couple of times and then summarized his main point. “The truth, Herman, is that without a protective shell, life will be far more confining than liberating.”

Both the irony and the reality of the situation were beginning to dawn on Herman. After thoughtful reflection, he turned to his dad and said,

“You mean that some things may seem to limit freedom but really make greater freedom possible?”

Fred smiled broadly and patted his son on the back with a mammoth claw. “How’d you get to be so smart, Son?” he asked.

This page is a part of a larger article and series of articles. Copyright © 2020 by B. Nathaniel Sullivan. All rights reserved.

Note:

1Josh McDowell and Bob Hostetler, Don’t Check Your Brains at the Door: Know What You Believe and Why, (Dallas: Word Publishing, 1992), 179-182.

image credit: Dr. James Dobson

image credit: hamster